Proving a Vision-Saving Treatment Works

Science Education

The information gleaned from ProgSTAR will be of enormous value in designing future clinical trials for Stargardt disease treatments.

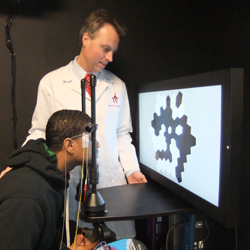

Dr. Hendrik Scholl conducts an electroretinogram, or ERG, with a patient at the Wilmer Eye Institute.

I am very excited about ProgSTAR, the Foundation’s new study monitoring and documenting the progress of vision loss and retinal changes in people with Stargardt disease. On the surface, the study might not sound very exciting, because it isn’t evaluating a potential cure. However, the information gleaned from ProgSTAR will be of enormous value in designing future clinical trials for Stargardt disease treatments.

Ultimately, it is as important to design a good clinical trial as it is to develop a good treatment. We could have the best treatment ever devised, but without a good human study to demonstrate its safety and efficacy, we’ll never obtain U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, to get it to the people who need it.

Designing a clinical trial for retinal disease therapies is challenging for many reasons. First, retinal diseases often progress slowly and affect vision in ways that are not easy to measure. Often, evaluating visual acuity by having someone read an eye chart doesn’t tell us if a treatment is actually saving vision. We may need to look at the person’s peripheral vision or ability to adapt to dark settings.

Observing structural changes in the retina itself may enable us to more quickly determine if a therapy is benefiting vision. Figuring out the best “outcome measures,” as we call them, for use in a clinical trial is one of the most important goals of ProgSTAR.

ProgSTAR will also help identify the best potential participants for a clinical trial of a Stargardt disease therapy. Will people with early-stage or late-stage disease be more likely to respond to a therapy? How long will we need to monitor them to observe a response? We need answers to these questions to implement treatment studies that are cost-effective and expedient.

Not only do we need the right patients for a clinical trial; we need good clinical researchers. The Foundation has assembled the world’s best Stargardt disease experts for ProgSTAR. Led by Dr. Hendrik Scholl, of the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins, these investigators are unmatched in their understanding of Stargardt disease, and participation in the study will advance their knowledge even further. Dr. Patricia Zilliox, the Foundation’s chief drug development officer, serves as project director. She is well-qualified, with more than 30 years of industry experience.

ProgSTAR is monitoring approximately 200 people enrolled at nine clinical centers. They will be monitored for two years, but researchers are also looking at retrospective data on patients to get a better picture of how the disease and vision loss progress. ProgSTAR is a “by invitation-only” party; investigators are recruiting only their existing patients to participate.

It is rare for a non-profit foundation to fund a natural history study, because they are expensive — ProgSTAR will cost at least $3 million — and they don’t provide an immediate return of a new therapy. But, as I’ve just explained, these studies are invaluable for moving treatments forward for inherited retinal diseases; they bring us a big step closer to a cure.